Bolivia’s Carreras Pampas reveals unprecedented dinosaur trackways

More than 16,000 fossilized footprints discovered in Bolivia offer a vivid window into the movements of theropod dinosaurs over 100 million years ago. These tracks, preserved along an ancient shoreline, provide rare insights into how these predators navigated their environment during the late Cretaceous period.

The Carreras Pampas site, situated within Bolivia’s Torotoro National Park, has revealed an extraordinary concentration of theropod footprints, with scientists recently identifying 16,600 impressions. This number exceeds any previously recorded tracksite in terms of sheer volume. The preserved tracks cover approximately 80,570 square feet (7,485 square meters) and include both isolated prints and continuous trackways, which trace the paths of individual animals. The study, published in PLOS One, represents the first detailed scientific survey of this remarkable site.

A busy dinosaur thoroughfare

Paleontologists refer to Carreras Pampas as a “dinosaur freeway,” where theropods repeatedly traversed through soft, deep mud between 101 million and 66 million years ago. It is suggested by researchers that the tracks, primarily oriented in north-northwest and southeast directions, were created over a relatively brief timespan, signifying that this region served as a commonly used passageway for these carnivorous dinosaurs. This dense collection of tracks implies a broader network of movement that might have spanned parts of Bolivia, Argentina, and Peru.

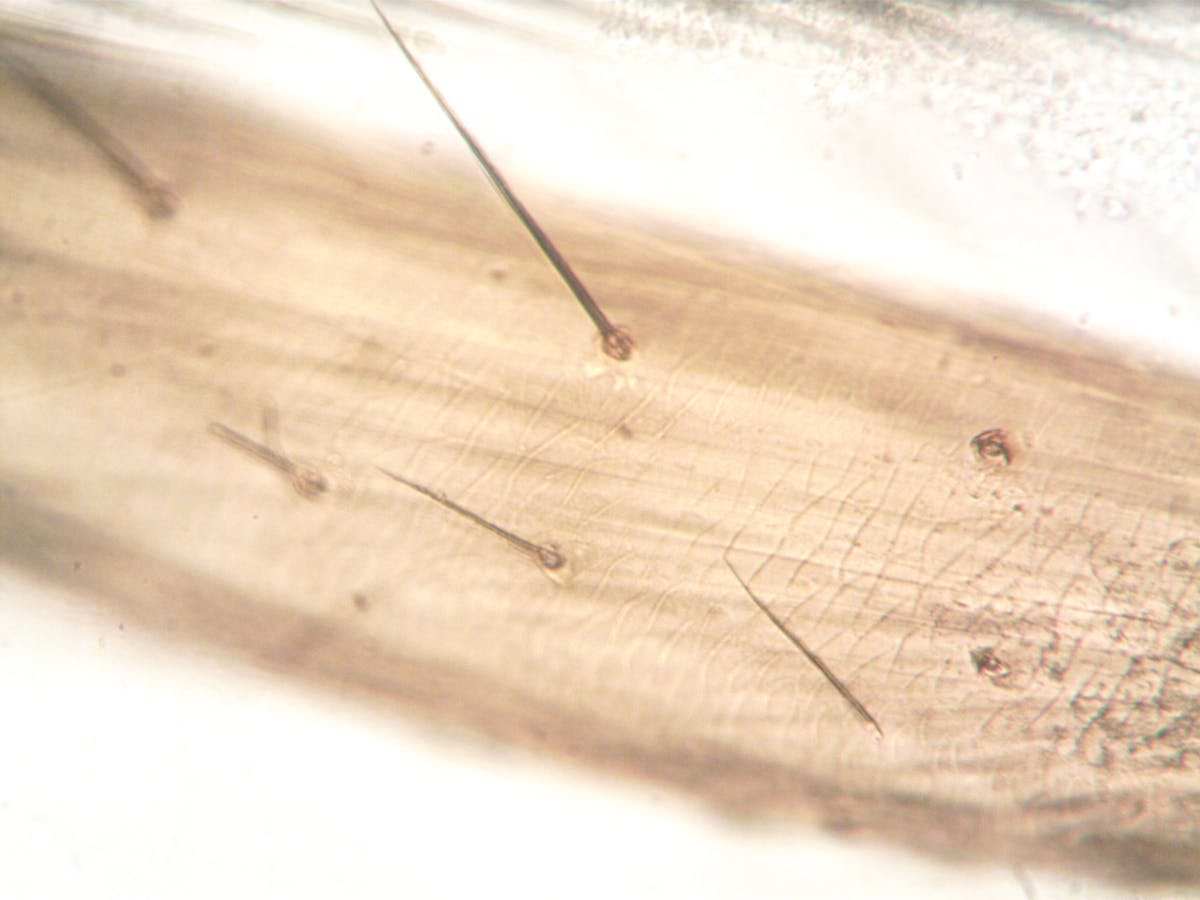

The size and spacing of the footprints reveal diverse behaviors. Some theropods moved leisurely along the muddy shoreline, while others sprinted, leaving longer, deeper impressions. Remarkably, over 1,300 tracks show evidence of swimming, with the middle toe pressing more deeply into the mud while the other toes and heel left lighter marks. These details offer a unique view into how dinosaurs interacted with water and navigated their surroundings.

Understanding derived from footprint measurements

Analysis of footprint dimensions reveals a broad spectrum of theropod sizes, with estimated hip heights ranging from approximately 26 inches (65 centimeters) to over 49 inches (125 centimeters). Some trackways even feature tail drag marks, offering further insights into the animals’ movements. Alongside the theropod tracks, researchers recorded several hundred bird footprints that coexisted along the shoreline, offering a window into the wider ecosystem of that era.

“The tracks preserve a detailed record of movement and environment,” said Dr. Peter Falkingham, a professor of paleobiology at Liverpool John Moores University, who was not involved in the study. “Deeper impressions capture the motion of the foot in ways skeletal remains cannot, revealing gait, posture, and interactions with the substrate.”

Swimming tracks, for instance, differ markedly from walking tracks, as buoyancy alters how the toes press into the mud. These subtle variations help paleontologists reconstruct behaviors that bones alone cannot convey. Dr. Jeremy McLarty, coauthor of the study, noted, “Tracks are a record of soft tissues, of movements, and of the environments the dinosaurs were actually living in. Carreras Pampas brings these lost ecosystems to life.”

Comparing trackways across Bolivia

Although Carreras Pampas has been recognized for its dinosaur footprints since the 1980s, the extent and concentration had never been systematically examined. Bolivia features numerous tracksites from the Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous periods, establishing it as one of the most abundant regions globally for dinosaur trackways. Before the Carreras Pampas survey, the most productive site was Cal Orck’o in Sucre, which contains approximately 14,000 tracks from around 68 million years ago.

The predominance of theropod footprints at Carreras Pampas raises questions about the ecosystem dynamics of the time. Unlike sauropods, which traveled in herds, theropods were typically solitary predators. This tracksite, dominated by carnivorous dinosaurs, may indicate localized hunting grounds or a migration route heavily trafficked by these agile hunters. McLarty emphasized, “When you start comparing across sites, you can begin to see patterns of dinosaur movement on a continental scale.”

Insights from trackways that fossils alone cannot provide

Unlike skeletal fossils, which may be displaced from their original locations after death, trackways provide a direct snapshot of life in motion. “A skeleton shows what an animal could do; trackways show what it actually did,” explained Dr. Anthony Romilio, a research associate at the University of Queensland. Trackways capture speed, direction, turning behavior, slipping, posture, and, in some cases, group interactions.

The Carreras Pampas site holds particular significance as it maintains a range of theropod sizes, potentially indicating various species or age categories. The richness and variety of footprints deliver insights into population composition, predator-prey interactions, and the manner in which distinct species coexisted within the same environment. The tracks further offer proof of recurrent usage over time, implying that this shoreline served as a crucial passageway within the Cretaceous landscape.

Consequences for paleoecology

By analyzing the depth, shape, and spacing of footprints, scientists can deduce not only the size and behavior of dinosaurs but also the properties of the substrate and the environmental conditions of that era. The soft, deep mud preserved at Carreras Pampas recorded subtle details like foot rotation, claw impressions, and tail drags, all of which shed light on how these creatures navigated their surroundings.

These discoveries have wider implications for comprehending the ecology of late Cretaceous South America. They assist in reconstructing predator-prey dynamics, shoreline utilization, and even possible seasonal trends in dinosaur migration. Moreover, the blend of theropod and avian tracks offers a more comprehensive view of the Cretaceous ecosystem, emphasizing the interaction between large predators and smaller species that coexisted.

Preserving a window into the past

Carreras Pampas showcases how trackways can capture snapshots of ancient life in a manner that mere bones cannot achieve. Visitors to the location are literally positioned where dinosaurs once trod, leaving a motion record that remains unchanged over time. McLarty remarked, “Tracks remain stationary. When you visit Carreras Pampas, you are aware that you are standing where a dinosaur once walked.”

The vast array and variety of footprints render this site an invaluable asset for continuous research. Future investigations might juxtapose Carreras Pampas with other Bolivian locations to discern regional trends in dinosaur behavior and movement. Through the mapping and examination of these trackways, scientists can gain a deeper understanding of how theropods traversed terrains, hunted, and engaged with both their own kind and other species.

Moreover, the site emphasizes the significance of safeguarding fossil trackways, which provide invaluable insights into ancient life. Every footprint depicts a brief moment from millions of years past, illustrating the dynamics of extinct creatures in a manner that skeletal remains cannot achieve.

The Carreras Pampas tracksite in Bolivia provides an extraordinary record of theropod activity and behavior, revealing the movements, sizes, and interactions of dinosaurs on an ancient shoreline. These fossilized footprints are more than just impressions in stone—they are vivid snapshots of prehistoric life, offering scientists and the public alike a rare opportunity to witness the Cretaceous world as it once existed. The detailed analysis of these tracks not only enhances our understanding of dinosaur ecology but also enriches the global picture of how these iconic predators shaped and navigated their environments millions of years ago.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(749x0:751x2)/Jared-Isaacman-329f219aed0e4faa8b341aa46849d3c2.jpg)