The Western cinematic category is characterized by expansive vistas, lone protagonists, intense confrontations, and clear-cut ethical dilemmas. However, a select number of movies have so profoundly transformed and exemplified the genre as The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966). Helmed by Sergio Leone and propelled by Ennio Morricone’s legendary musical composition, this motion picture has not only attained a devoted following but has also re-envisioned the fundamental principles of Western narratives for audiences globally. A close look at its storytelling framework, visual methodologies, societal impact, and enduring heritage clarifies why it is frequently regarded as the quintessential Western.

A Revolutionary Approach to Storytelling

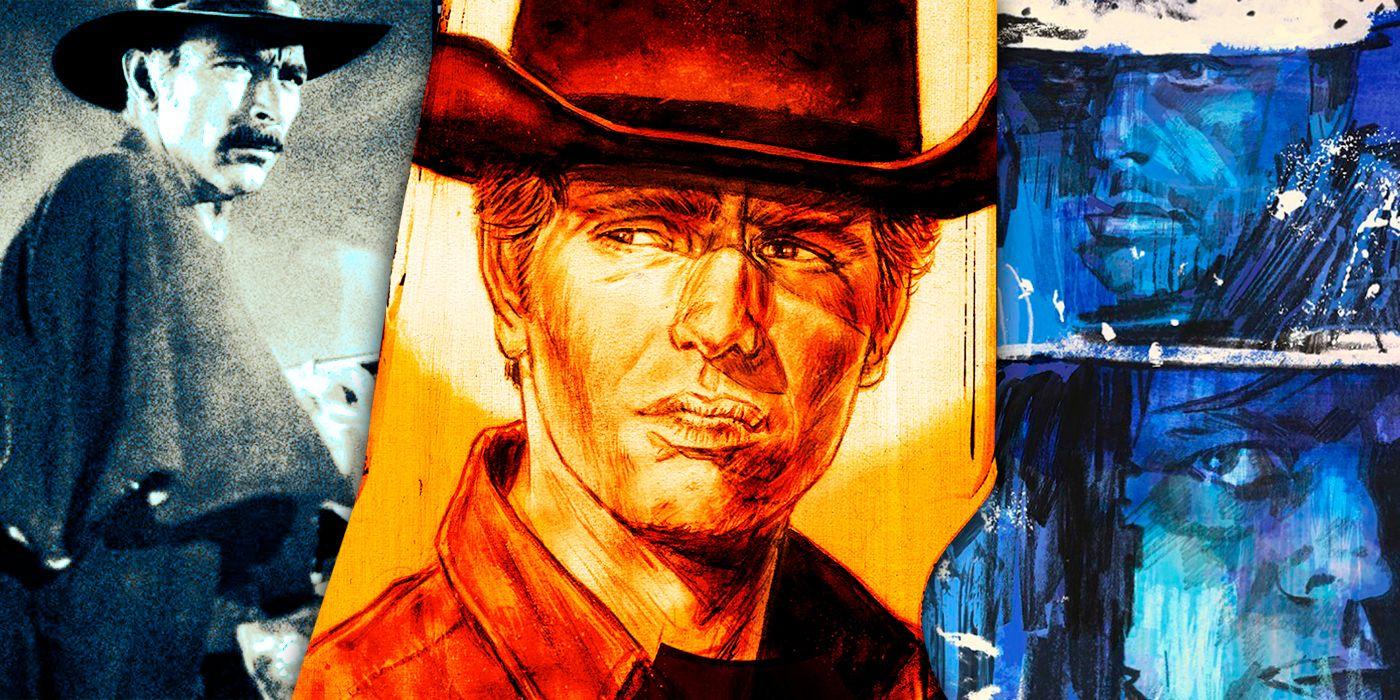

At its heart, the movie’s brilliance stems from Sergio Leone’s audacious challenge to conventional character molds. In this narrative, the distinctions between good and evil are masterfully obscured. The three main figures—Blondie (the Good), Angel Eyes (the Bad), and Tuco (the Ugly)—do not merely stand as stark moral contrasts, but rather as intricate, imperfect, and unpredictable personalities. None of them personify the archetypal virtuous cowboy or the unequivocally wicked outlaw seen in previous Westerns. Instead, each character is driven by their primal urge to survive, their avarice, and their distinct personal principles.

Leone crafts the storyline around a quest for hidden riches amidst the American Civil War, positioning the broader conflict as a setting rather than the primary focus. This approach allows the filmmaker to highlight the individual paths and evolutions of the main figures. The story intricately blends their drives and loyalties, culminating in an iconic three-way confrontation—a scene that has since been emulated countless times in film.

Visual Storytelling and Iconic Cinematography

Leone’s visual sensibility is revolutionary for its time. The director’s use of extreme close-ups juxtaposed with vast landscape vistas creates an experiential tension unique to the film. Cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli employs natural light to accentuate the dust, sweat, and grit etched into each character’s visage, enhancing realism while also building mythic resonance.

Perhaps the film’s most celebrated visual sequence is the climax at Sad Hill Cemetery. Through rapid editing, shifting perspectives, and excruciatingly prolonged silence, Leone generates an almost unbearable suspense. The dance of eyes and hands before the gunfire is not mere theatrics but an embodiment of psychological warfare, forever altering how shootouts are conceptualized on screen.

Rewriting the Soundscape: Ennio Morricone’s Score

If Leone reimagined the visual lexicon of Westerns, Ennio Morricone fundamentally altered their auditory landscape. The central musical motif of the movie, distinguished by its coyote-esque cries, eerie whistles, and unconventional instrumentation, stands as one of the most iconic scores ever created. This musical composition transcends mere accompaniment; it operates as a driving narrative element, intensifying feelings, delineating personalities, and occasionally even punctuating the unfolding events with a theatrical magnificence.

Morricone’s musical compositions for every principal character—a distinctive whistle for Blondie, a melodic flute for Angel Eyes, and expressive human voices for Tuco—function as aural leitmotifs, deepening their portrayal and inner lives without requiring explanatory conversation. The collaborative effort between the director and the composer in this movie established a lasting standard for the fusion of music and cinematic art.

Ethical Complexity and the Frontier Legend

Most earlier Western films idolized the frontier, casting the West as a place where good could triumph over evil in a lawless environment. Leone’s film challenges this myth, presenting the Union and Confederate armies not as paragons of virtue or villainy, but as institutions capable of senseless violence and corruption. The futility and chaos of war loom constantly in the background, rendering the treasure hunt both absurd and existential.

The complex morality of the main trio exposes the thin line between good and bad when survival and greed rule. This ambiguity creates a more authentic reflection of the human condition, encouraging audiences to question black-and-white worldviews and the simplistic heroics associated with classic Westerns. The American West in Leone’s hands becomes a metaphor for life’s randomness, danger, and ambiguity.

Influence and Imitation: Setting the Standard

The movie’s impact extends beyond its category. Filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino, Martin Scorsese, and the Coen Brothers have acknowledged its foundational role. The “Mexican standoff”—made famous by the graveyard finale—is now a worldwide cinematic symbol for suspense, deception, and fluctuating authority.

In addition, the film gave rise to the “spaghetti Western” subgenre, inspiring dozens of European and American productions that adopted Leone’s stylistic and thematic codes. The gritty realism, anti-heroic protagonists, and moral complexity became staples, eventually bleeding into American neo-Westerns, revisionist interpretations, and even unrelated genres, from science fiction to graphic novels.

On a technological level, Leone’s experimental editing, use of widescreen Techniscope format, and innovative blending of soundtracks laid the groundwork for modern action cinema, influencing editing rhythms and sound design in contemporary blockbusters.

An enduring cinematic masterpiece

Multiple layers of artistry converge in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. The film’s narrative intricacies, psychological characterization, visual grandeur, and sonic ingenuity form a holistic cinematic experience. Its commentary on violence, morality, and the unpredictability of fate resound even beyond its Western backdrop, offering a timeless meditation on human nature and power.

Through relentless innovation and fearless storytelling, Leone’s masterpiece refuses to fade into nostalgia. Instead, it endures as a touchstone—one that continues to challenge, entertain, and inspire. As each new generation re-engages with its dust-blown duels and existential questions, the film remains not just a pinnacle of Western cinema, but a landmark in the global language of film itself.